I finished the manuscript of my book, finally.

It all began about a year ago.

About a year ago, I was approached by the literary agent Kanishka Gupta. He asked if I’d be interested in writing a book and whether I had something that could be pitched. At the time, I’d been obsessing over Indian internet culture but I didn’t want to write anything from the grand TED Talk version where the internet is either toxic or we must all return to the offline world to rediscover ‘real connection.’ That binary of Toxic online world and non toxic offline world always felt shallow. I was more interested in the subcultures—the absurd, the strange, the deeply human pockets of the internet that operate like digital folklore. I believed that if we paid attention to these fragments, we might begin to ask a better question—not whether the internet is good, bad, or ugly, but whether it is, in the words of peacemaker Donald Trump, “a place where people use common sense and great intelligence(™).”

Some people say writing a book is like running a marathon. Murakami explores this in great detail in the only book of his I like—What I Talk About When I Talk About Running. Yes, at first, the distance seems absurd, almost impossible. But once you begin, everything around you starts to blur, and you just keep running. That’s more or less true. After a while, the process and the ritual of work consume you far more than the idea of the finish line.

It reminded me of Bernard Moitessier, a sailor who was on the verge of winning the 1968 Golden Globe Race, one of the most grueling solo sailing competitions in the world. (I even did a podcast episode about him, which you can listen to for free [here].) Moitessier had already conquered the hardest part. He had survived storms, was nearing the finishing line, and was poised to win. Then he did something that still makes ambitious people uncomfortable. He turned away from the finish line. He sent a note to the race organizers saying he was heading to Tahiti “to save his soul.”

It sounds like one of those over-the-top metaphors I usually try to avoid. But there’s something in it, especially when it comes to creative work, that’s hard to ignore.

I think about that often, especially now, after finishing the manuscript. At one point, the end felt impossible to reach—but somewhere along the way, the finish line stopped mattering. The rewrites, the late edits, the days of staring at broken arguments stopped blocking the work and slowly turned into the work itself. After the initial struggle, it was no longer about getting through them. It was about living with them. It was like those mosquitoes that hover around you at night. You know they’ll annoy you, but you also develop a strange lust for the mosquito racket. You start craving that sharp, perverse sound of one more insect getting electrocuted.

Also, I realised that finishing a book is mostly a psychological game. It’s an endurance test. It’s not just about ideas, thoughts, or what you put into a Google Doc. You have to deal with a whole range of emotions, especially the voices in your head. The hardest among them is disgust. The moment you write something, a voice whispers that it’s awful. That you’re wasting your time. That you’re a worse writer than you thought. These questions don’t visit you occasionally. They live in the room like hidden jinns. And still, somehow, you keep writing. You learn to treat those voices like the drilling sound in the next apartment. Loud, annoying, and eventually, in John Cage’s wisdom, just part of the background music.

Then there’s the question of consistency: what to choose—the discipline of routine or the romanticism of inspiration? I used to belong to the second camp. A few years ago, if I accidentally wrote something good, I would stop writing for months. The idea that you’ve created something decent in this chaotic world is oddly terrifying. But eventually, I realised that, too, is a kind of indulgent romanticism. If you want to create more, you have to forget that idea of purity of emotions. You show up, stick to a schedule, and take what the day gives you. Good, bad, mediocre, masterpiece—they're all part of the same protocol. It’s like casting a net into the sea: whatever turns up, turns up.

Meditation helped. So did the slow acceptance that no feeling lasts forever—not joy, not despair. That sense of impermanence gave me a bit of detachment, which allowed me to keep working. Of course, it sounds profound in theory and collapses in practice. Some days, serenity is a form of punishment. There are mornings when you want to pick a fight with the silence, vandalise your own peace, just to feel alive again.

There’s also the deeper, more stubborn question: why create anything at all? What can be the motivation to create? This past year was chaos, in both good and bad ways. The world we live in has a talent for breaking illusions. You realise the artists you once admired aren’t that remarkable. The music you used to love starts sounding repetitive. The intellectuals turn out to be petty people with big vocabularies and ikea furniture. Writers you found interesting reveal their narcissism in long interviews—as if they’re auditioning for the role of God. The less we talk about the influencers around us, the better. Everything feels like we are living in the age of mass disillusionment, a cultural flatline.

And yes the world in general feels angrier, more violent. One could argue that it has always been this way, and perhaps it’s true. The difference is that now we see it unfold in real time, often while lying in bed. Cruelty now has better distribution. Violence no longer arrives as delayed history but plays out live on our phones, wrapped between ads and influencer reels. You move from a bombing to a skincare routine in three swipes.

And yet, in the middle of this flood, you’re supposed to sit down and do something creative. Write a sentence. Edit a video. Sketch an idea. It feels ridiculous. But somehow, that's what you try to do.

What does it even mean to search for beauty through creation when the world is collapsing? How do you motivate yourself to sit down and do creative work when every part of you is asking—for what?

And yet, somewhere in that question is also the answer. You don’t create because the world makes sense. In a collapsing world, creation is just a way to make personal sense of the chaos.

Also, throughout this process, Substack really helped me maintain consistency in my writing practice. And through it, I found real-time feedback and some truly wonderful people. When I started writing on Substack, a lot of people told me not to do it for free. “You shouldn’t put anything out without getting paid,” they said. I understood the concern. But at that point, the urgency of what I wanted to write about mattered more than strategy. I also needed a space where I had some degree of freedom, and the pressure was less about performance and more about practice.

And in a short time, this platform gave me something I wasn’t expecting- a community of dedicated readers. That became one of the main reasons to keep writing. The last time I checked, over 30,000 people were tuning in monthly, which feels absurd considering that five years ago, I was on the internet writing things that barely two people read.

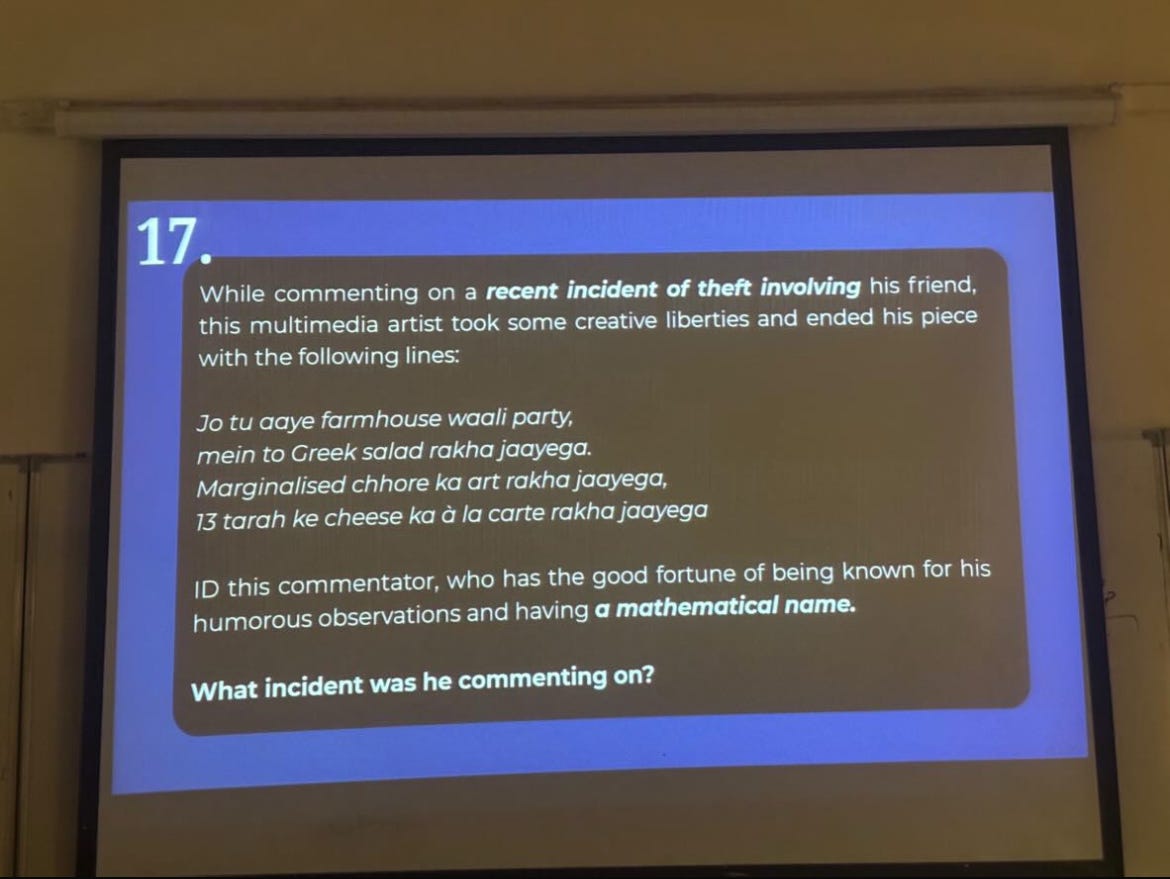

I’ll write more about the book process soon. But here’s something interesting: a friend from Delhi University recently sent me a photo from a quiz competition at Miranda House. One of the questions was based on my substack article about Amir Aziz and the art gallery theft.

Anyway, the point of this post was that I finished the manuscript and the book is slated to be released later this year, published by Bloomsbury. I’m genuinely excited to share what I’ve been working on over the past year. More on that soon.

Also here is 🎙️ Members-Only Episode. In a time when war became a spectacle and fake news ran wild, I sat down with Ravikant Kasana aka Buffalo Intellectual to unpack the India–Pakistan faceoff, media’s meltdown, and who won the narrative war.

Now streaming for members.

Also

itney saare sach ek saath likhne ki kya zaroorat thi, Anurag minus Verma?!

I can't wait to read your book. Your essays are very calming. In a world full of texts meant to excite, provoke, and outrage, your essays work like a soothing balm. Thanks for writing.