So how will you remember 2025 ?

The Paradox of memory

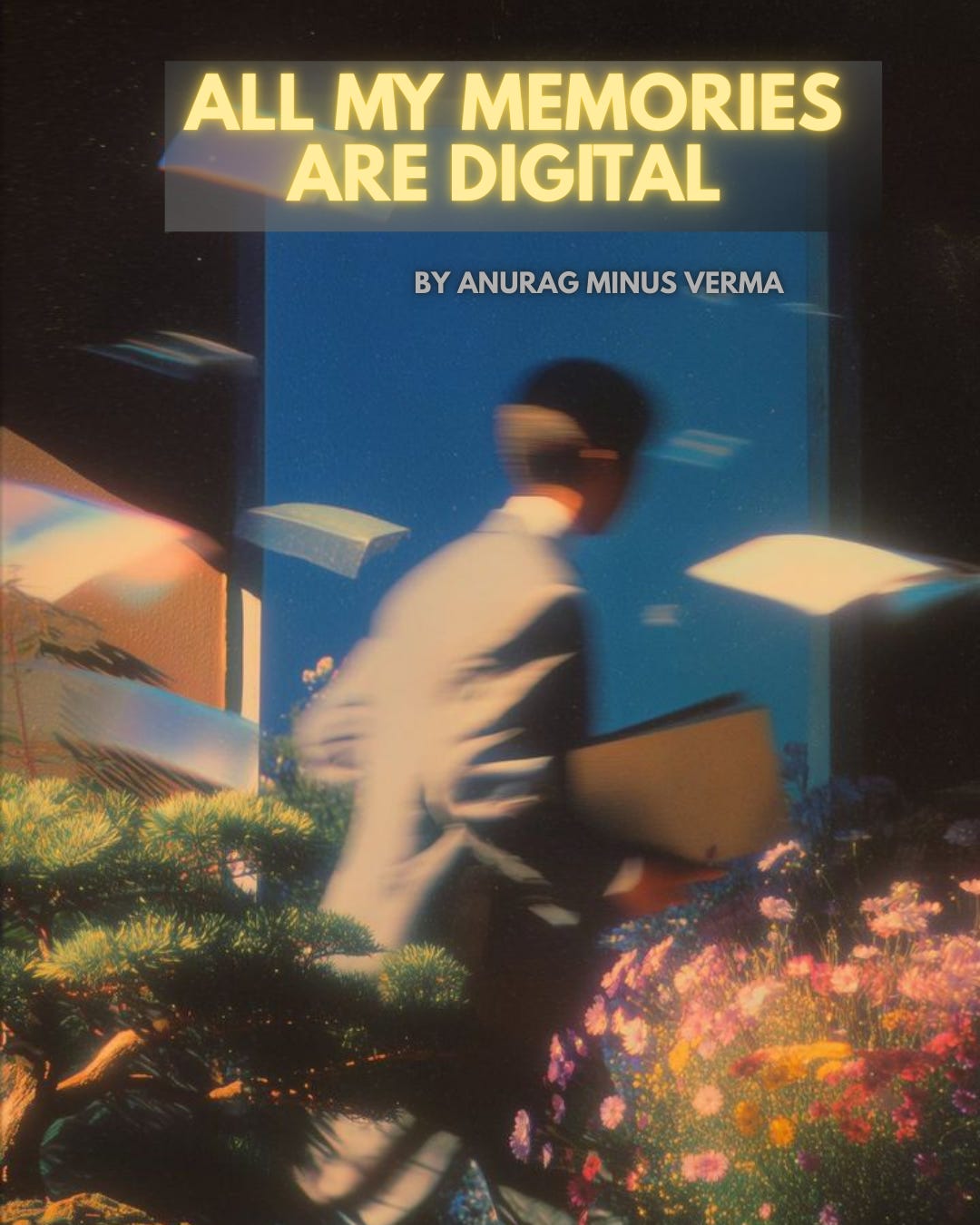

A few days ago, a media organisation asked me to write a yearender for 2025. The brief was to summarise the cultural and political moments that defined the year. I agreed without thinking much. It sounded like a harmless exercise, a way to rewind the year and impose some order on it. Then I sat with the idea for a few days and realised I could not write a single line.

The reason became clear soon enough. I had two honest responses.

First, I barely remembered most of what had happened this year. Second, whatever I did remember did not feel worth revisiting. I vaguely recall the Kamra incident and the breaking of a studio, but there is nothing left to say about it now. I remember the days around Operation Sindoor, when I lived with an anxiety that missiles could enter my Noida apartment at any moment. Even that period does not evoke any real interest, either for me or for a reader. There were many such moments. None of them ask to be revisited. Even thinking about them induces a yawn. They already feel stale, like infographic news from an Instagram page that was deactivated years ago.I stared at In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust, sitting on my bookshelf like a moral accusation. It reminded me that he was a romantic man who treated memory as something sacred, stretching it into volumes of such length and density that I have never managed to finish them.

That struggle of writing also pushed me to think about memory itself. Espcially the memory in the times of social media included brain-fog and oversimulation.

There is something strange about how we remember. Memory is not linear, but we keep forcing linearity onto it. I am often asked a question that exhaust me- “tell us about your journey.” The person asking imagines a neat movement from point A to point B. Life does not work like that. You may start at A, reach Y, then fall to T, return to A, and stay stuck there for years. It is more a game of snakes and ladder than a Vande Bharat ride (or perhaps it is an Indigo flight)

This is why if anyone question you about your personal highlights of 2025 then it may create a small internal panic. You begin auditioning moments in your head, searching for events that felt like achievements. The thought that this may have been another wasted year is scary. So the awkward silences, the idle gazes at sunsets, the long spells of nothingness, and the low grade confusion are erased, even though they probably explain the year far better than any achievement. A yearender demands coherence. Life rarely supplies it.

To compensate for this failing memory, we now outsource remembering to apps. Yearly wraps arrive to tell you who you were. Spotify assigns you a listening age. YouTube claims to know you through your viewing history. Even ChatGPT now offers a wrap. Every platform works on the same belief: you are what you consume. Personality is reduced to data and choice that you made on those apps. The wandering of your thumb defines you.

At the same time, consumption itself begins to manufacture memory.

Every year I wait for meme rewind videos. These edits pull together viral templates and accidental moments into something surreal, almost like an alternate reality we all inhabited. Memes travel through circulation and repetition, picking up meaning along the way, until they settle into shared references among friends. They turn into a language. The rewind captures something official yearenders never manage. It brings back its mood, the absurd rhythms, and the nonsense through which most of the time was actually spent.

This also reveals how completely the border between online and offline life has dissolved. When I meet people who live intensely on Twitter (often called as Twelebs), conversation rarely escapes that platform. Everything is recalled through tweets, pile ons, cancellations, and fleeting victories of viral quote tweets. For them the world outside the timeline feels irrelevant, almost unreal. Their memories are digital memories which are formed according to what trended and what vanished. It is tempting to treat this as a personality flaw, and some of it is grating, but it is no longer unusual. It is simply how memory now learns to organise itself in the online world.

Even for those who are not creators, only consumers. That line too is fading. Posting an Instagram story is creation. Commenting is creation. Entire pages now exist that turn comments into content. On social media, to exist at all is to create, and in the same breath, to be converted into content yourself.

In this over-simulated world, memories become less physical and more digital. We have entered a phase where memory itself is outsourced. I often rely on Facebook Memories to understand who I was one or two years ago. Sometimes I cringe. Sometimes I am amazed by a great line I wrote. It becomes a strange kaleidoscope of humiliation and ego in equal measure. Google Photos does something similar. It reminds you where you ate, who you were with, the hotel bed, the food plate, the face that has aged, the one who have lived with you and one who now left forever. The world has moved on and traces remain.

When memory is stored outside the body, experience begins to feel second hand. Nothing stays long enough to bruise or to comfort. One moment replaces another before it has time to settle. Nostalgia too feel stripped of ache or warmth, producing neither special sadness nor special delight. In this endless overwrite, the sacredness of memory collapses. We are freed from remembering and slowly become hostages of the present. Topicality turns into the only reality, and there is a kind of lightness in that. But every freedom comes from a loss. In gaining ease, we may have lost the burden that once gave memories that made us feel more human. Perhaps if Proust were born in this age, he might be ordering Biscoff on Blinkit, less interested in remembering than in producing a new digital trace, posting a story with caption- In Search of Lost Clout.

If you liked the piece then consider ordering my book here:

'I am a very interesting person online' read this on a tshirt today

Axis Bank app also has a yearly rewind now. The first 2 slides are how much you invested and your transactions. And the next 3 slides are quizzes on how Axis Bank did in terms of deposits made, mutual funds bought, etc. Basically it made the year mainly about itself 😂